The US Supreme Court has taken up two cases against affirmative action in college admissions. Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina are a pair of lawsuits which aim to remove race and ethnicity as possible considerations for college admissions.

A quick look at both cases identifies the plaintiff in both as Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., an organization founded by Edward Blum. Blum is a man who has found his singular mission in life, to remove any legal system which preferences minorities. He is identified as a “litigant” and he matches potential plaintiffs up to suits he would like to move forward. He gained a bit of notoriety in 2012 when he helped Abigail Fischer bring a case against the University of Texas for using affirmative action in admissions, while simultaneously helping Shelby County, AL to overturn laws which prevented it from changing its election laws out of fear that they would disadvantage minorities.

He lost the Fischer case, but the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Shelby County, and the results haven’t been great for black voters.

But in spite of losing the high profile Fischer case, Blum is back and he is determined. And this time the composition of the Supreme Court leans far more in his favor. And unlike the court’s ruling on abortion, a lot of American’s have changed their beliefs on this topic too.

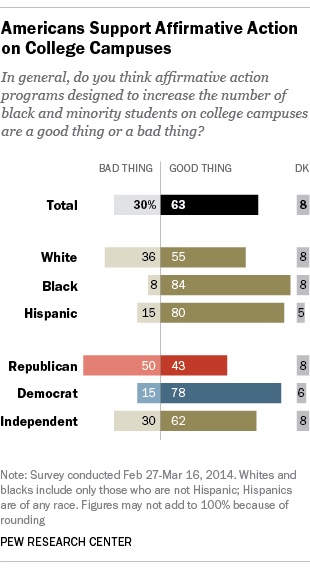

The poll on the right by PEW Research was from 2014, and it showed fairly strong support for affirmative action. This is in contrast to the recent Washington Post poll below, which shows fairly strong support for banning it. While it is possible that poll design changed the way respondents answered, it is also likely that narratives around affirmative action have helped to remove support for it. And that has implications for how effective affirmative action can be.

Affirmative action is tricky because, like climate change, opponents have done a good job of making the science seem questionable. Most notoriously, the idea of “mismatch” is brought up, claiming that minority students are actually hurt by affirmative action. The term was coined by Richard H Sander in his 2004 paper about affirmative action in American Law Schools. The theory is that students who get admitted into schools that they don’t necessarily qualify for on the basis of race will then not be as prepared as peers who didn’t have that experience and perform worse in school, leading to generally worse outcomes. This idea is so common that it led to a 2012 book by Sander that was referenced by former Justice Scalia in the Fischer trial.

It makes a certain kind of sense to think that students could find themselves in a university that exceeds their skill level and feel out of their depth, and that “little fish in a big pond” experience could lead them to do worse in schools, and eventually to do worse in their careers. But recent literature does not support Sander’s claims.

Because while the Supreme Court is deciding whether all schools can consider race in admissions, there are already many schools which cannot.

There are currently nine states where public institutions and jobs cannot consider race in an application. These came around at different times (Idaho just passed the ban in 2020), and many were done via ballot measures. California, for instance, passed Prop 209 in 1996 and then failed to repeal it when prop 16 failed in 2020. So a black student applying for college in 1997 had a different landscape than one applying in 1995.

If mismatch theory was right, underrepresented minority students (URM), as the paper calls them, would land in schools which were more reflective of their abilities, excel harder, and wind up in higher paying jobs. This did not happen. Instead, qualified URM students, who might have gotten in, were deterred from applying, and the students who landed at lower-tier schools did not rise to the challenge and excel in their “matched” environment.

In many ways this kind of confusion helps those who want to feel upset about affirmative action. A white student in 2022 who is rejected from UCLA (a California public school) might see a URM classmate be accepted to UCLA and assume that they only got in based on race, not aware that UCLA doesn’t consider this. They might have even heard of USC (a California private school which is allowed to consider race) accepting affirmative action students and not understand the difference.

So even though there are vocal opponents, like Edward Blum, there is too much good research which highlights that it can be effective and that the benefits outweigh the costs to continue to believe that it is debatable whether it helps underrepresented minorities.

But the Supreme Court cases focus on fairness and that is a far more sticky wicket. How fair or unfair is admission to Harvard? It is so selective that they are ultimately choosing between lots of different students who are all theoretically qualified. There are few students who are admitted with lower than a 4.0, and those that do aren’t dominated by racial minorities. In fact, the strongest way to preference yourself as an applicant is not to be a racial minority, but to be a legacy, an athlete, or related to staff or donors.

For some reason this doesn’t rile the public’s ire as much as affirmative action. We might never know why.

More Stories

Tutoring as a part of teaching / Everything comes back to money

One of the difficult things with education is our reliance on a “one size fits all” model. We have for...

Justin Reich on Learning Loss, Subtraction in Action, and a future with much more disrupted schooling

Justin Reich is an education and technology researcher and the director of MIT’s Teaching Systems Lab. He hosts a podcast...

Public K-12 Enrollment is falling and that is dangerous and exciting

A surprising result of COVID and the resulting school closures is that many parents, after struggling to figure out how...

Esports could help re-diversify a shrunken curriculum

Esports and schools feel like a pretty strange fit. Regular sports have always gone with schools, but adding esports still...

Review of “How to Raise Successful People” by Esther Wojcicki

This is an interesting book with the perspective of a unique person that ultimately falters because of the blind spots...

SIGGRAPH at 50

SIGGRAPH , the premier conference on computer graphics education, held its 50th event last week in Los Angeles. Back in...